On the Principal Proportions in Architecture

Of the necessity of proportions.

If I were to ask anyone which structure they prefer, I am sure the second one would be the one selected. It has a sound, regular composition, in stark contrast with the other which is a disorganised mess of colours and shapes. It is certainly folly then, not to observe and apply sound proportions to any construction.

Of the nature of a System of Proportions.

Proportions are important, but what proportions must be used? Two major ones will be used here, that of music and that of the Golden Ratio.

It may be surprising to modern ears, but music as we know it is the result of a system elaborated by Pythagoras two thousand and five hundred years ago. Many commentators relate that the famous mathematician arrived at four of them by pinching a tensioned string. They are 2:1, an octave; 3:2, a fifth; 4:3, a fourth; and 9:8, a tone. To these were added during the Renaissance and modern times, 15:8, √3:1, 5:3, √2:1 and 5:4 . These form the basis for the notation in use today and prevent discordance between notes.

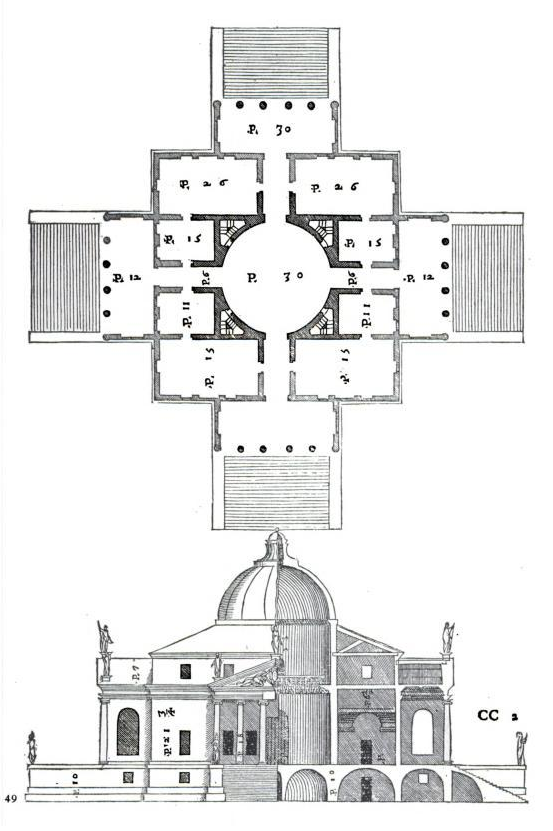

Many early architects, seeing that these proportions make music the most beautiful, concluded that they would also lead to beautiful architectural compositions, for both sight and hearing are both senses. It was on this conjecture that many of them built, for instance, Palladio in his Villa Rotonda:

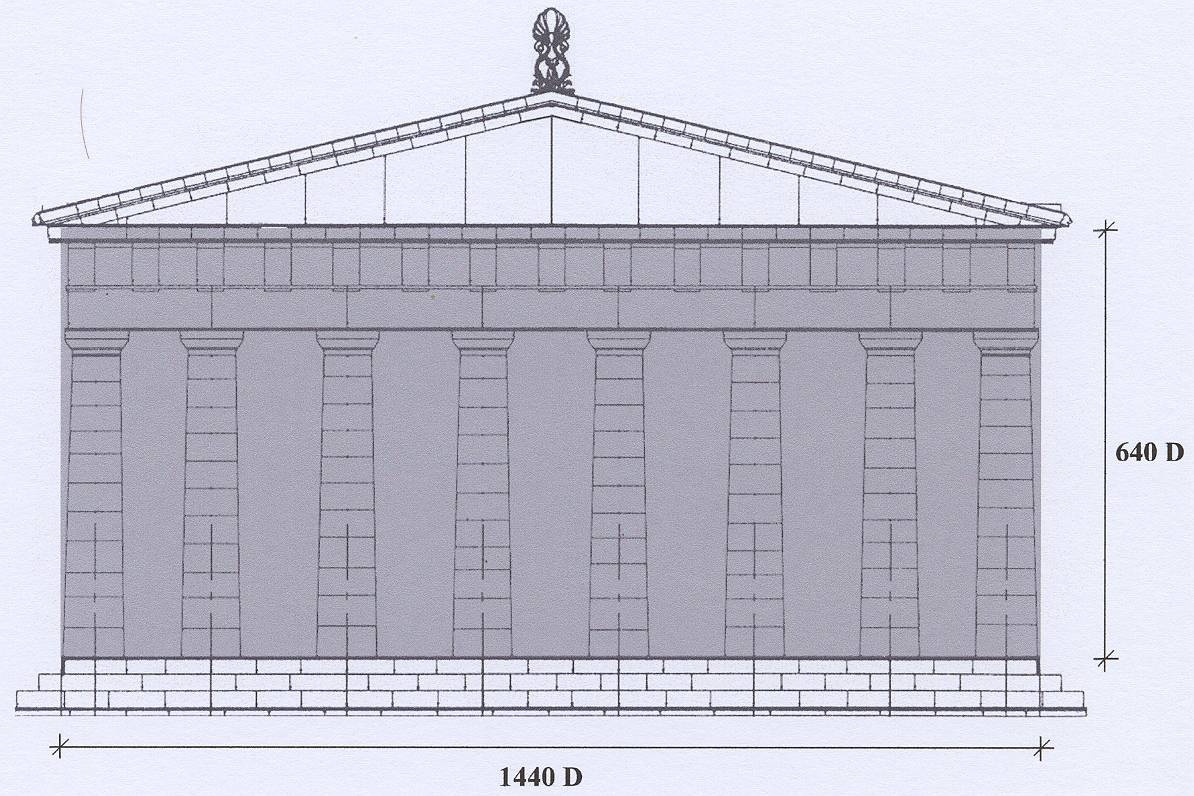

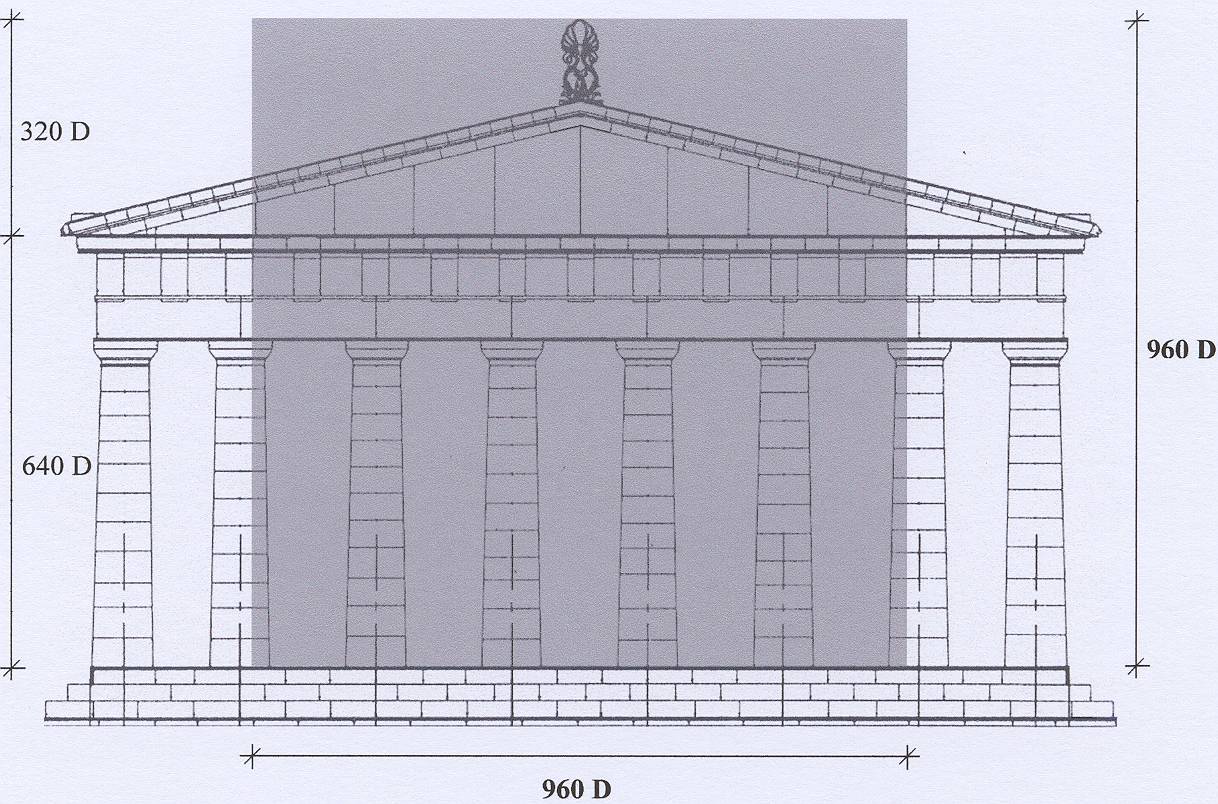

The other system, well less attested but infinitely more popular, is that of the golden ratio, φ, which is approximately 1.618, and which is defined as the limit of the division of two adjacent numbers in the Fibonacci sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 89, 144, ... ). Many people claim this is a “sacred” number, due to its apparent manifestation in the ratios between legs and arms, &c. The Parthenon is the most famous of the purported applications of this number:

It turns out, the Parthenon used 9:6:4 (or 3:2!). Oops!

While it is true that the golden ratio was known to the Greeks and the Romans, there is very little evidence that supports the claim that they used it actively in any of their structures, and the “proofs” that exist can very well be attributed to clever camerawork or simple coincidence (there are many parts of the body to choose from – one can find any ratio with it!).

The set of musical ratios may be preferred to the Golden ratio for many reasons, the first being that they are many while there is only one golden mean, permitting greater diversity (only using the golden mean will ensure a monotonous composition); the second, that they are used actively and proven to be harmonious; &c.; &c.

Proportions in Action

These masterpieces all obey fixed rules and yet are able to invite very different attitudes to them: the parlour feels homely even if it is really quite lofty; the Senate House, in its smallness, manages to radiate a great pomp; Saint Peters radiates importance, yet its imposing facade is at the same time massive and inviting, being done with elements such as windows that would really be adequate only to building twenty times smaller!

An idea seems to have taken hold in the minds of many, that the artist is one working without limits, or seeking to change them. But this is not the case, for just as painters have had to work with the very specific constraints of nature, perspective and paint, and still gave future generations masterpieces to admire, so must the architect, but with the constraints of geometry (proportions), vision and technology.

Proportions Applied to the Horizontal Component of Buildings (floor plans, &c.)

Proportions Applied to the Facades and Exteriors of Buildings